We’re making a film trailer for an asteroid-themed space thriller starring our daughters and while it completes post-production, I’m telling the story!

Once the interior set was mostly complete, we turned our attention to the exterior shots of space. We’ll start with the starship model and its original metallic-flake candy paint, as well as go over how we made all the tiny little asteroids.

Click here to read Part One — Building the Interior Set

Shipbuilding

The specs for the ship were based on a design the girls came up with and hastily scribbled on a napkin for me. I got three napkin views of the ship and another drawing of what the engines would look like.

I built the ship’s body out of a subdivision surface, which basically means that I was able to use a set of 3D points to roughly shape the surface and then let the computer figure out how to position all the the smaller polygons that form the body.

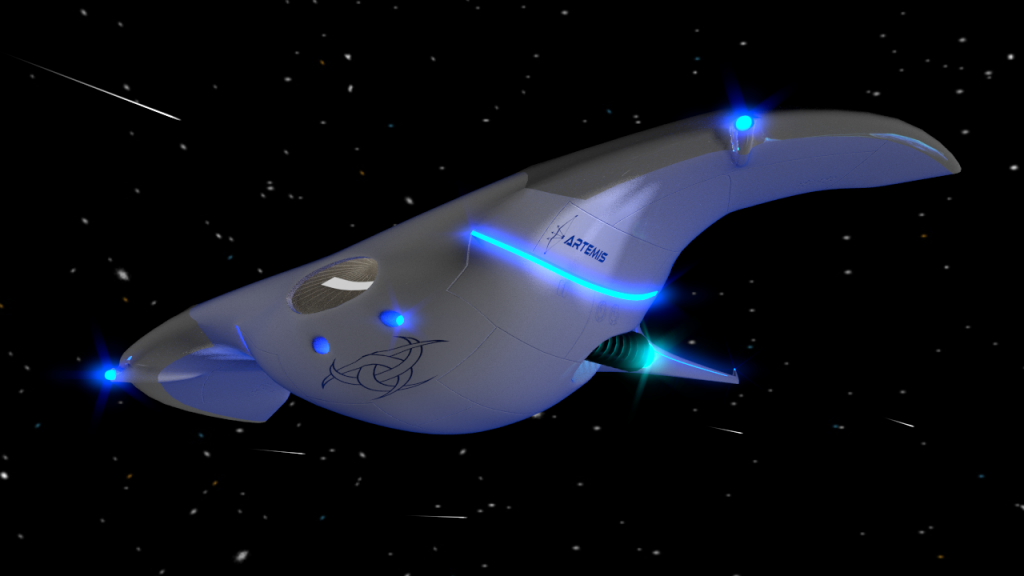

The ship structure matched the napkin design very well, accurately capturing the “flying stingray” concept that I think the girls were going for. This meant it was time to come up with some cool space paint to cover it and if you’re going to cruise around the galaxy in a giant stingray, I thought you should do it with a hot rod paint scheme.

These were the early paint materials I developed that I thought were super-awesome. Like an expensive hot-rod paint job, one produced different colors depending on the angle at which it was viewed and simulated the inclusion of reflective metal flake embedded in the paint. At the first design review, however, I received the following creative feedback:

- Not red

- Lose the flake

- Too shiny

I simplified the chameleon paint to be white with only a tinge of blue along the edges. The sparkly flake just didn’t work for such a large object and I cut the shininess down by half. While we may have lost some sex appeal, I had to admit that the new look was a lot more like a professional space operation.

As with the interior set, increased realism comes with the addition of details. We added some panel seams, hatches and fuel ports using bump mapping that created indentations in the surface of the ship and I added a couple of decals from Ken who, among his many roles on the project, is also the Art Department.

Ken also suggested the two spotlights under each wing to illuminate the name “Artemis” which I thought really looked cool when they were done. We added some glow and glare around the lights and the ship was ready for it’s voyage to the heart of asteroid country.

Exteriors

Since the ship design incorporated aerodynamic wings, it was clear that we were taking more of a cartoon-style approach to our version of space. I liked this direction because the lighting in space kind of stinks and the decision allowed us to take some additional artistic license in other areas as well.

Thus it was that we were able to increase our ambient exterior lighting as well as provide a secondary “fill” sun to reduce the harsh non-photogenic shadows of space. We also added retro-looking particles that would stream past the starship while it was hightailing it though space. This was my idea and I admit now that it was mostly to show off the reflections in the ship’s paint job.

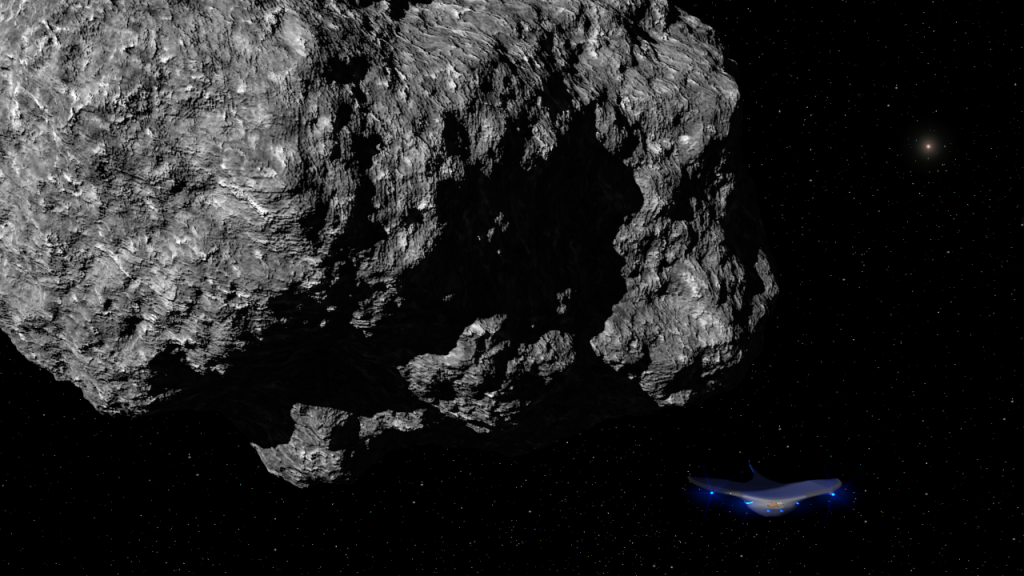

The large asteroids were created by taking a primitive mesh and giving it both a displacement map at the geometry level to create the large bumps, as well as a texture bump map as part of the shader to make the small cracks and fissures.

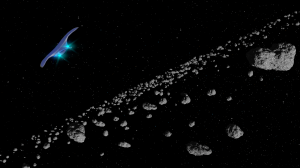

The smaller asteroids were made by taking small versions of the larger asteroids and generating a thousand of them using a particle system to spawn the asteroids across the viewing area with slightly random velocity and spin. In one scene, I used a vortex force to coerce the asteroid particles into a slow orbit around a planet.

So with the vast majority of the asteroids animated by the particle system, we were able to concentrate on animating the handful of “real” asteroids that were part of the story.

All of the asteroid scenes actually had to be captured twice, once using the native Blender renderer for all the asteroids and then again using the newer Cycles renderer for the now-somewhat-less-fancy-but-still-way-sexy ship paint. We used a matched camera in both scenes and then composited the frames together in a post-process so they looked like they were in the same shot.

Check in next week when we (finally!) get around to putting the girls in the picture— but be forewarned that the geeking around with computers will continue unabated.

Click here to read Part Three — Integrating Live Action

We didn’t find the astoierd in 2029. We found the astoierd YEARS ago, and because we can do advanced math, we have a pretty good (but not exact) idea of where it’s going to be in 2029.Things whiz past us all the time that we only see when they happen, or even sometimes after they happen, because we didn’t know they were coming, and they were so small that they were hard to pick up if you weren’t looking for them.(Most astoierds are discovered by chance a telescope happens to be looking in the right place at the right time, and sees one that’s never been seen before.)Once we’ve observed an astoierd a few times, we can predict its orbit and figure out where it’s going to be with a fair amount of accuracy.Now, planets are different, because they’re HUGE, and reflect a lot of light. They’re easy to see, and they’d bet VERY easy to see a new one coming out of nowhere, even decades away.Therefore, the only reasons we might not see something today that is supposedly going to be here in 2012 are:1. It’s very small.or2. It doesn’t exist.It’s simply not possible that we would miss a planet-sized object cruising through the outer solar system, on the way to earth. Everyone on the planet would be able to see it.Heck, you can see Jupiter’s 4 big moons with a decent pair of binoculars, and one of them is smaller than our Moon. (And Jupiter is a lot farther away than 3 years, even if it suddenly stopped going around the sun and headed straight for us.)The only rational conclusion is that the 2012 object does not, and can not, exist.However, this answer will probably be thumbs-downed by a couple of totally irrational people.